DET006 - Mapping Detroit: The Evolution of Boundaries, Private Claims, and Military Reserves through 1876

- Patrick Foley

- Feb 11, 2025

- 5 min read

The historical development of Detroit can be traced through its evolving maps and shifting boundaries, each reflecting the city’s transformation from a fortified outpost to a structured urban landscape. The earliest known maps of Detroit were produced by Joseph Gaspard Chaussegros de Léry, a French lieutenant and engineer, in 1749 and 1754. These plans, later copied in 1845 by Jacques Viger of Montreal and subsequently acquired by Detroit historian C.I. Walker in 1854, depict the fortified settlement in its infancy. The only notable differences between the two maps are the minor extensions of the stockade and the addition of key structures such as a bakehouse and a storehouse in the 1754 version. The cemetery, marked in the 1749 map, does not appear in the later plan. A striking feature of the 1749 map is its resemblance to the earliest maps of New Orleans, suggesting a shared French colonial approach to urban planning.

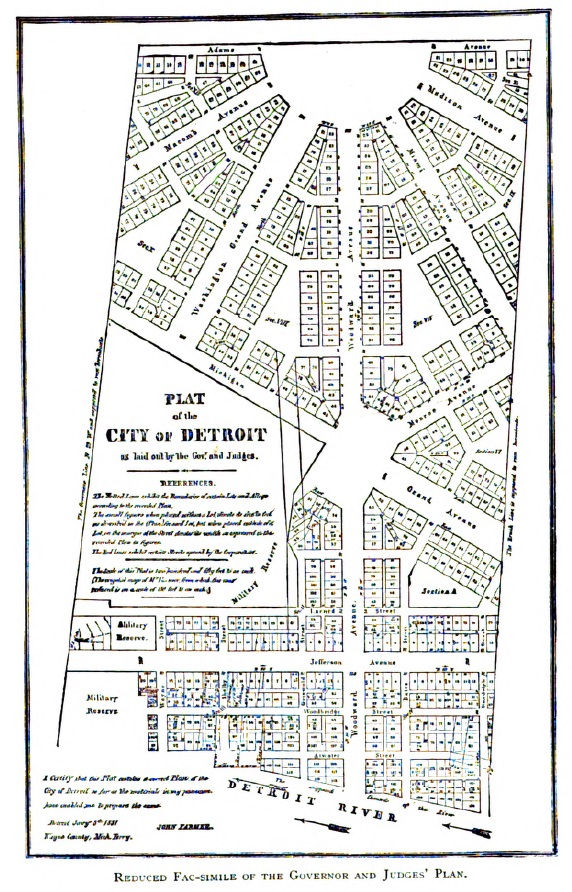

The next significant map was produced in 1816 by T. Smith, providing a detailed representation of Detroit as it existed in 1796, shortly before the British relinquished control. This map, later owned by Eugene Robinson in 1877, was based on notes obtained from the U.S. War Department. It became the foundation for later maps, including those published by A.E. Haethon in 1846 and 1856. Additional maps followed in the 19th century, such as John Farmer’s 1835 map, which was the first to accurately delineate the sizes of lots and land claims. These maps played a crucial role in defining property lines, planning public infrastructure, and settling legal disputes over land ownership.

Detroit’s city boundaries have changed multiple times throughout its history, reflecting both the growth of the settlement and political struggles over land. In 1803, Indian Agent C. Jouett wrote to the War Department, noting that of the 225 acres granted to Cadillac in 1701, only four acres were occupied by the town and Fort Lernoult. The remainder of the land, except for a 24-acre addition to William McComb’s farm, remained a common area. The Act of 1802 defined Detroit’s boundaries as extending from the Detroit River two miles inland, with specific delineations at the division lines of prominent landowners such as John Askin and Pierre Chesne.

However, the boundaries were repeatedly revised. On October 24, 1815, the city limits were expanded to include the Cass Farm for a distance of two miles from the river. Just five years later, the Act of March 30, 1820, removed the Cass Farm from the city limits once again. The Witherell Farm was included in the city’s jurisdiction in 1836, only to be excluded again in 1842. Further boundary extensions took place in 1873 when parts of Hamtramck and Greenfield were annexed, but this expansion was later declared illegal by the Michigan Supreme Court. In total, the city’s boundaries were curtailed four times and permanently extended seven times.

Among the many land claims that shaped Detroit’s development, the Cass and Brush farms are among the most frequently mentioned. These large tracts of land bounded the original Governor and Judges’ Plan—Brush Farm lying to the east and Cass Farm to the west. Portions of the Cass Farm date back to land grants made in 1747 to Robert Navarre and in 1750 to Barrois, Godet, and St. Martin. By 1781, Jacques St. Martin’s portion of the farm was sold at auction to William Macomb for £1,060. Over time, additional acreage was added, forming what became Private Claim No. 55 and Private Claim No. 592, both confirmed to John, William, and David Macomb in 1807 and 1808, respectively.

Governor Lewis Cass acquired the property in 1816 to meet the legal requirement that territorial governors own at least 1,000 acres of land. At the time of purchase, the Cass Farm extended to the banks of the Detroit River, with its southern boundary near what is now Jefferson Avenue and Second Street. In 1836, significant grading efforts removed 25,000 cords of earth to level the land, paving the way for urban development. That same year, a syndicate purchased the Cass Farm for $100,000, but its remote location from the city center led to slow sales. By 1841, the land between Larned Street and Michigan Avenue was subdivided, with further divisions north of Michigan Avenue in 1851 and north of Grand River in 1859.

The Brush Farm followed a similar trajectory. Originally conceded to Eustache Gamelin in 1747, it was later transferred to Jacques Pilet in 1759 and then sold to John Askin in 1806. Elijah Brush acquired the majority of the property in 1806, and the land was gradually developed into residential lots by 1835. Many of these lots were leased rather than sold, with rental rates periodically adjusted based on new appraisals. By structuring sales and leases to require high-quality construction, the Brush and Cass families ensured that their land became prime real estate, attracting affluent residents and shaping Detroit’s urban landscape.

Military land holdings played a crucial role in the early development of Detroit. When the British surrendered Detroit in 1796, the fort, citadel, and surrounding military installations became property of the United States government. The Governor and Judges’ Plan incorporated these lands, but federal authorities retained control over the military reserves, preventing the city from utilizing them for civic development.

In 1824, Congress transferred the Military Reserve between Larned Street and Jefferson Avenue to the city, with the exception of the arsenal and storekeeper’s lots. Two years later, an additional grant included Fort Shelby and its surrounding grounds, on the condition that Detroit construct a powder magazine outside the city limits. The powder magazine was built along Gratiot Road, near what is now Russell Street, and completed in 1831.

The city officially took possession of the Military Reserve on September 11, 1826, and by April 4, 1827, the Legislative Council authorized the Common Council to alter the Governor and Judges’ Plan for land north of Larned Street, south of Adams Avenue, and between Cass and Brush Streets. Property owners affected by this reorganization were either assigned new lots or compensated for their losses. Despite protests from local citizens, the plan proceeded, and a public auction of lots on the former fort site took place on May 16, 1827. The conditions of sale required that a two-story stone, brick, or frame house be built on each lot before the final payment was due—failure to comply would result in forfeiture of the property.

For several years, some of the old fort buildings were repurposed as rental properties, with the city acting as a landlord. These efforts marked the gradual transformation of Detroit’s military stronghold into a structured urban environment, with former fort lands integrated into the growing cityscape.

The history of Detroit’s maps, land claims, and military reserves provides a detailed account of the city’s complex evolution. From its earliest days as a French outpost, Detroit’s development was shaped by shifting boundaries, private land claims, and contested government decisions. The Governor and Judges’ Plan, the annexation and removal of various farms, and the eventual incorporation of military reserves into the city all reflect the ongoing struggle to balance land ownership, urban growth, and civic planning.

Detroit’s expansion was not merely a matter of natural growth but the result of calculated legal decisions, real estate speculation, and civic negotiations. The legacy of these early maps and land disputes is still visible today in the city’s layout, where historical land claims and old boundaries influence modern property lines and neighborhood divisions. The transformation from a frontier fort to a bustling city was neither linear nor uncontested, but it laid the foundation for Detroit’s future as a major American metropolis.

Comments