DET005 - Detroit’s Public Lands: The Governor and Judges’ Plan, the Park Lots, and the Ten-Thousand-Acre Tract

- Patrick Foley

- Feb 11, 2025

- 5 min read

The story of Detroit’s land development in the early 19th century is one of dispute, ambition, and controversy, centered around the public domain and the authority exercised by territorial officials. From its earliest days under French control, much of the land surrounding Fort Pontchartrain had been used as a common field, a practice that allowed Detroit’s residents to cultivate land collectively while maintaining individual allotments for farming. This communal land system persisted into British and American rule, with the residents of Detroit holding a long-standing belief that the commons rightfully belonged to them. However, as Detroit transitioned from a small military outpost into an organized settlement, questions over ownership, public use, and government authority over land became increasingly contentious.

Following the American acquisition of Detroit in 1796, the status of the commons came into question. Unlike private landholdings, which were often granted through formal deeds, the commons were considered public land, controlled collectively by the town’s inhabitants. Yet, with the establishment of American governance, military and government officials began asserting control over these lands, leading to disputes with local residents.

In 1797, Quartermaster-General John Wilkins Jr. wrote to Secretary of War James McHenry, emphasizing the strategic and economic importance of Detroit’s vacant land. Wilkins warned that unauthorized settlement on the commons could pose risks to both military security and orderly development, advocating that the land either be strictly regulated or sold off in organized lots. The letter also revealed the precarious nature of land ownership in Detroit—many residents had occupied land for years without formal legal title, leaving their claims vulnerable to government intervention.

Despite these early concerns, no immediate action was taken. Inhabitants of Detroit continued to use the commons for farming and pasture, operating under the assumption that the land belonged to them. This belief was reinforced in 1802 when the Northwest Territorial Legislature formally instructed its delegate to Congress, Paul Fearing, to secure official confirmation of Detroit’s commons as public land for the benefit of its residents. However, Congress failed to act on the request, leaving the status of the land unresolved.

The situation changed dramatically in 1805 when a devastating fire swept through Detroit, reducing nearly the entire town to ashes. With most of the town’s structures destroyed, the question of land ownership became urgent—both for those seeking to rebuild their homes and for territorial officials attempting to reorganize the city.

In response, the U.S. Congress passed the Act of April 21, 1806, granting the Governor and Judges of Michigan Territory the authority to lay out a new town plan for Detroit and manage a ten-thousand-acre tract of land surrounding the settlement. The goal was to provide land to displaced residents while using additional land sales to fund the construction of public buildings, including a courthouse and a jail.

Under the leadership of Governor William Hull and Judge Augustus Woodward, the Governor and Judges’ Plan was conceived as an ambitious attempt to transform Detroit into a well-planned city. Woodward, heavily influenced by the grand design of Washington, D.C., envisioned a network of wide streets, diagonal avenues, public squares, and a circular layout that would accommodate future growth. His plan, finalized in 1807, included key features such as the Campus Martius and Grand Circus Park—elements that remain part of Detroit’s urban fabric today.

However, the execution of the plan was fraught with controversy. Many residents had hoped to rebuild on their original lots, but the new layout often placed streets or public spaces where homes once stood. Furthermore, the Governor and Judges exercised near-total control over land distribution, making decisions without consulting local inhabitants. The lack of transparency fueled resentment among those who felt they were being displaced from land they had long considered their own.

One of the most contentious aspects of the Governor and Judges’ land management was the handling of the Park Lots, a series of parcels north of what is now Adams Avenue. These lots were originally part of the commons and were expected to remain available for public use, primarily as grazing land for livestock. However, in 1809, the Governor and Judges began selling off the Park Lots at public auction, a move that infuriated residents.

A petition was submitted to the territorial government in 1811, urging officials to annul the sales and formally designate the land as a commons for public use. The petitioners argued that their ancestors had held and worked this land for over a century, long before the United States or even the Governor and Judges had any authority over Detroit. They insisted that the land had been promised to them by previous French and British administrations, though no formal documentation of such grants could be produced.

The response from the territorial government was a firm rejection. The Governor and Judges refused to annul the sales, and the process of subdividing and selling the land continued. For many Detroit residents, this was seen as a betrayal—an effort to push them off land they had cultivated for generations. One particularly outraged citizen lamented that Detroit’s original settlers were now forced to repurchase their own land “at twenty times the price” in a humiliating and unjust process.

Beyond the Park Lots, the Ten-Thousand-Acre Tract was another major component of Detroit’s land reorganization. This land, surveyed in 1816, was divided into a series of large parcels ranging from 80 to 160 acres each. While the official purpose of the tract was to support Detroit’s expansion, much of the land fell into the hands of wealthy speculators rather than ordinary settlers.

The Governor and Judges controlled the sale and distribution of these lands, and accusations of favoritism and corruption were common. Many residents believed that the officials prioritized land sales to politically connected individuals, rather than ensuring fair distribution. The donation lots, which were meant to compensate those who lost homes in the fire of 1805, became a particular point of contention. Some recipients later found themselves stripped of their grants due to bureaucratic rulings, while others sold their lots quickly in speculative deals.

By the 1830s, frustration over land distribution and mismanagement led Congress to demand greater oversight. The Governor and Judges had been expected to report on their land dealings, yet no formal records had been provided, and key details about land sales and revenues remained missing. Many Detroit residents suspected that officials had enriched themselves through questionable transactions.

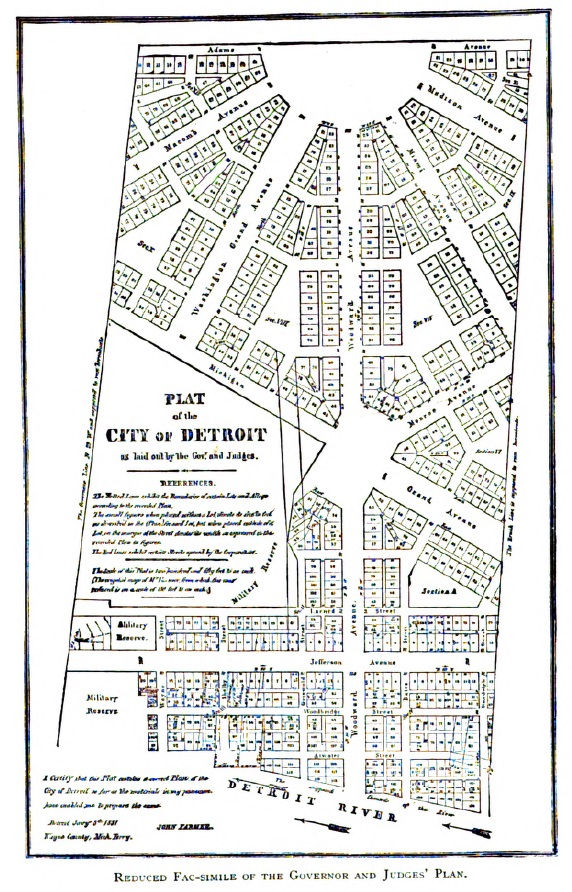

In 1831, Congress required the submission of an official city map, which was prepared by surveyor John Farmer. This document provided the first clear depiction of land ownership and public spaces under the Governor and Judges’ plan. However, despite this effort, concerns over corruption and transparency persisted.

Finally, in 1836, the Governor and Judges' authority over Detroit’s public lands was formally terminated. The city government assumed control over remaining land issues, though disputes over titles and boundaries continued for years. Even decades later, legal battles over land grants, commons rights, and disputed sales reflected the lingering impact of the Governor and Judges’ administration.

Detroit’s early land history is a story of ambition and conflict, shaped by competing visions for the city’s future. The Governor and Judges’ Plan laid the foundation for Detroit’s modern layout, yet it came at the cost of bitter disputes and deep divisions among residents. The sale of the commons, the handling of the Park Lots, and the management of the Ten-Thousand-Acre Tract left a legacy of mistrust that would shape Detroit’s governance for decades.

Despite these conflicts, elements of Woodward’s vision endure in Detroit’s streets, parks, and public spaces. The debates over land ownership, public use, and government authority in the early 19th century mirror larger struggles that continue to define urban development today. Detroit’s transformation from a military outpost into a major American city was not just a matter of economic growth—it was a battle over land, power, and the right to shape the city’s destiny.

Comments